Information Retrieval: the Great Search for Knowledge

In our modern information society, data, facts, and knowledge have a much higher priority than they were half a century ago. Thanks to the internet, information is more and more accessible. When we access information, it has been retrieved from online sources, which is where search engines come in. How do they find the information they provide us? The answer is called “Information Retrieval”. Gathering information – more precisely, information recovery – is a discipline in computer science and information science and, above all, of great importance for search engines. Using complex information retrieval systems, they recognize the intentions that are behind specific search terms and find relevant data on search queries.

The History of Gathering Information

Information retrieval is about making existing knowledge accessible. This has been the case since long before the dawn of the digital age. Vannevar Bush, one of the first people who seriously considered how humanity can make their concentrated knowledge more accessible in the face of an ever-changing world, published a groundbreaking article at the dawn if the information age (1945) titled: “As We May Think”. The article presented a vision for the future of information gathering and organization.

Bush saw the following problem in the sciences: experts are specializing more and more, and need more information – but because of the differentiation caused by this extreme specialization, the information is increasingly hard to find. Of course, this was at a time when libraries were still organized with analog paper boxes and large catalogs. A keyword search was only possible if a diligent librarian had already bothered to manually index all works. Bush saw a way to make his own information more accessible using the technical developments available at the time, such as microfilm. His vision was to create a Memex, which was a machine as big as a desk that would serve as a vault for knowledge, and become a serious piece of research equipment. The Memex was never built but the technology (users jumping from one article to the next) can be seen as a forerunner of hypertext.

In the 1950’s, the computer scientist Hans Peter Luhn dealt specifically with the task of obtaining information and developed techniques that are still relevant today: full-text processing, auto-indexing and selective information processing (SDI) have their roots in his research. These methods were very important for the development of the Internet as information retrieval systems are essential for navigating the oceans of available information on the internet. Without them, you would never be able to find the answers you are looking for.

Information Retrieval – a Definition

The aim of information retrieval (IR) is to make machine-stored data discoverable: unlike data mining which extracts structures from online records, IR is concerned with filtering specific information from a set of data. The typical application is an Internet search engine. Information retrieval systems solve two central issues:

- Vagueness: User inquiries are often inaccurate. The search terms entered by a user often leave a lot of room for interpretation. For example, those who search for the term “bank” may be looking for general banking information or may require directions to the nearest financial institution. The problem is compounded when users themselves are not sure what information they are looking for.

- Uncertainty: Contents of stored information are sometimes unknown to the system, which leads to users being presented with the wrong results. This happens, for example, with homonyms –words that have multiple meanings. The user might not be looking for a financial institution but information on a geographical feature relating to rivers.

In addition, the information retrieval system should also evaluate information to provide users with a data sequence. The first result should ideally provide the best answer to the users’ question.

Different Models

There are various information retrieval models that are not necessarily mutually exclusive and can be combined with each other. Some of these models only differ slightly in details. However, they can all still be roughly categorized into three groups:

- Set Theory Models: Similarity relationships are determined by set operations (Boolean model).

- Algebraic Models: Similarities are determined in pairs: documents and search queries can be represented as vectors, matrices or tuples (vector space model).

- Probabilistic Models: These models establish similarity by viewing the data sets as multi-stage random experiments.

Below, we will introduce the three archetypal models using these categories. The existing models above are all hybrids of the three types. Therefore, the extended Boolean model has the properties of set theory, as well as algebraic models.

Boolean Model

The most popular search engines on the web are based on the Boolean principle. These are logical links that help users refine and pinpoint a search. With AND, OR or NOT (AND, OR, NOT) or the corresponding symbols ∧, ∨ or ¬ a request can be specified when, for example, both terms should appear in the result, or content with a certain term should be hidden. These keys also work on Google, according to the same principle. The disadvantage of this system is that it doesn’t contain any ranking system for its results.

Vector Space Model

In a mathematical approach, content can also be represented as vectors. In the vector space model, terms are mapped as coordinate axes. Both documents and search queries receive specific values related to the term and can be represented as points or vectors within a vector space. Subsequently, both vectors are compared to each other. The vector (or content) closest to that of the query should appear first in the result rankings. The disadvantage here is that without Boolean operators, no terms can be excluded.

Probabilistic Model

The probabilistic model makes use of probability theory. Each document is assigned a probability value. The results are then sorted according to the probability with which they fit each search. How high the chances are that a certain content corresponds to a user’s wishes is determined by so-called “relevance feedback”. For example, users may be asked to rate the results manually. At the next identical search, the model will show a different (perhaps better) result list. A disadvantage of this procedure is that it starts with two requirements, neither of which are guaranteed. On one hand, the model presupposes that the users are willing to participate in the system by giving feedback. On the other hand, the theory also assumes that users view the results independently of one another, evaluating the content of each source as though it were the first they had read in the search. In practice, users always value information based on previously viewed content or held knowledge.

Operating Principles or Information Gathering

With information retrieval, different methods and techniques are used, independently of the models. The goal is always to simplify information searches for the user and to deliver more relevant results.

Term Frequency, Inverse Document Frequency

The importance of a term for a search query is calculated by combining how often a term occurs and the inverse document frequency. The value is abbreviated as tf-idf.

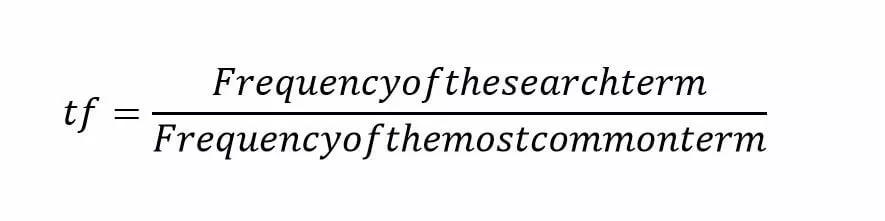

- Term Frequency: Search word density indicates how often a term appears in a document. However, how often a term appears cannot be a sole indicator of how relevant a text is, as some texts may contain the word multiple times due to length, rather than relevancy of content. Therefore, the frequency should be calculated in relation to how big the document is. To do this, how often the search term appears is divided by how often the highest-frequency word appears (eg. “and”):

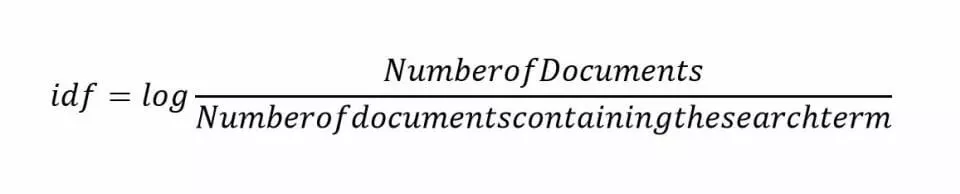

- Inverse Document Frequency: In IDF, the complete body of text is considered, rather than just a single document. Words that are only found in few documents will have a higher relevance than terms which appear in almost all texts. For example, the term “inverse document frequency” has a high higher value than “and”.

By combining the two tests, information retrieval systems can provide better results than if they were used alone: if it were just the term frequency that was important, then the search query “The TV show with the mouse” would prioritize content in which the words “the” and “with” appear. That would obviously be unhelpful. In contrast, if the inverse document frequency is used, “TV show” and “mouse” are much more important for the search and are recognized as the actual search terms.

Query Modification

A major problem in information gathering is the behavior of users themselves: wildly inaccurate requests bring up incorrect or inadequate information. To avoid this, information scientists have introduced query modification, a system that automatically changes the entered search query. That means, for example, that synonyms are used which provide better results. The system makes use of thesauri and user-feedback to find those synonyms. To avoid depending on user-cooperation, they can use so-called “pseudo feedback”. With this method, the system reads related terms from the best search results and rates them as relevant to the search. Inquiries can be extended or improved by using the following techniques:

- Stop Word Elimination: Stop words are those expressions that only contribute insignificantly to the content of a text. It makes sense not to treat words like “and” or articles such as “the” as representative of the document’s content.

- Multi-word group identification: Groupings of words must be recognized as such. This identification ensures that the search engine also considers parts of compound words to be relevant.

- Root and Root Shape Reduction: To search more effectively, words must be reduced to their root words. Otherwise, inflectional forms of a word would not appear correctly in the search results.

- Thesaurus: In addition to the terms used in the relevant document, an information retrieval system should also consider synonyms of the word as relevant. This is the only way to ensure that users find what they are looking for.

Recall & Precision

The effectiveness of an information retrieval system is commonly calculated using the factors recall rate and precision. Both are represented as quotients.

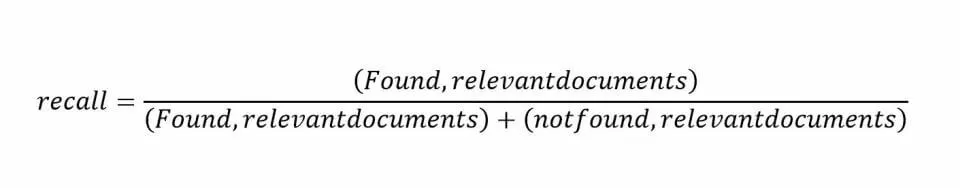

- Recall: How complete are the search results? To do this, the number of “found, relevant” is compared with the number of “not found, relevant documents”. The quotient, in other words, indicates how probable it is that a relevant document will be found:

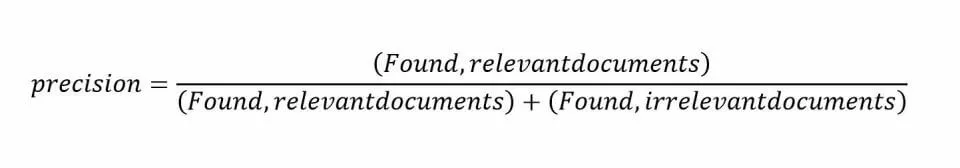

- Precision: What exactly is the search result? To ascertain this, the number of found, relevant to the number of found, irrelevant documents is provided. The quotient indicates how probable it is that a found document is relevant:

Both values are basically between 0 and 1, where 1 would be a perfect value. In addition, perfect results are excluded for both quotients in practice. Those who increase the completeness of the search result do so at the expense of accuracy and vice versa. Additionally, the fallout (i.e., the default rate) can be calculated as an additional value: this quotient reflects the false positive rate; it is determined by the ratio of found, irrelevant documents to irrelevant contents that were not found. Recall and precision can be represented as an axis diagram in which each of the two values occupies one axis each.

Information Retrieval: Example of a Search

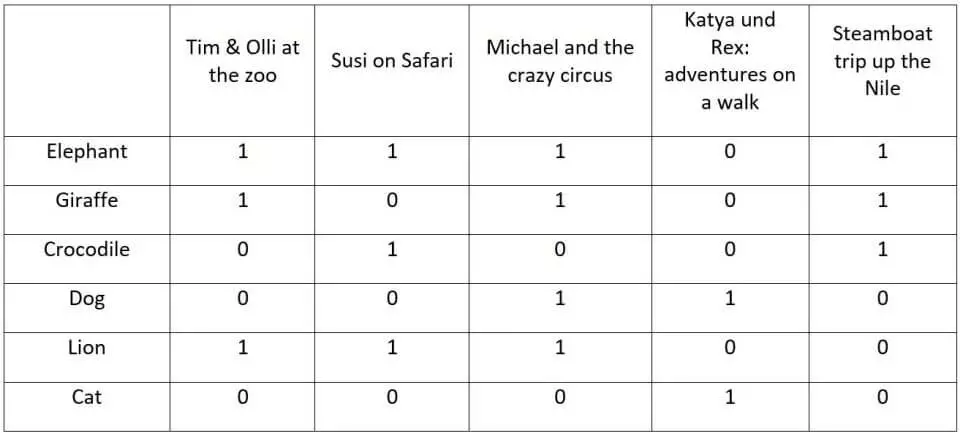

Every internet search engine is based on information retrieval. Google, Bing, and Yahoo are examples of prominent computer-aided information gathering. However, to show how IR works in practice, it makes sense to take a simpler example of our own. Take a search matrix in a (very small) children’s library. There are animals in all the books, but we only want to find books which feature elephants and giraffes, and no crocodiles. A search with the Boolean method would look like this: elephant AND giraffe NOT crocodile. The result of the search can only ever be 1 or 0: Does the term occur, or not?

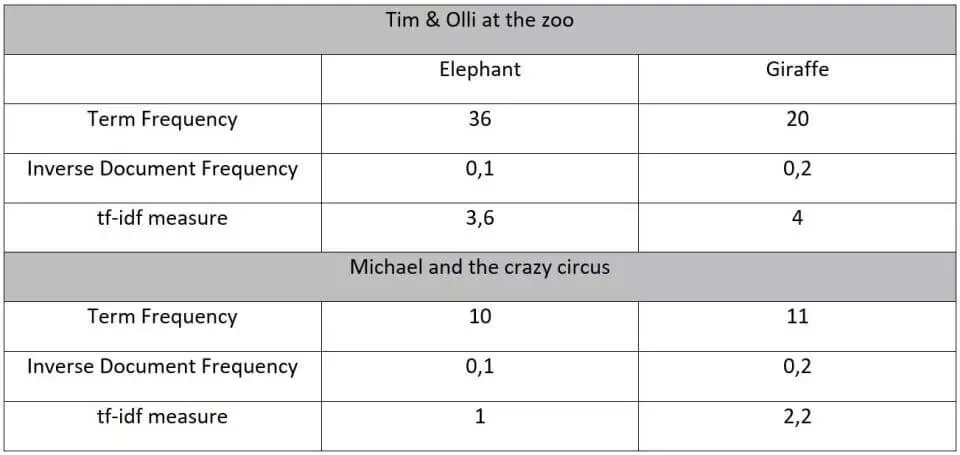

The result of the search would be “Tim & Olli at the Zoo” and “Michael and the Crazy Circus”. However, it does not weigh the results. Which book is more about elephants than giraffes? To ascertain this, the system can determine the Term Frequency and the Inverse Document Frequency.

“Tim and Olli at the Zoo” is probably the right answer when looking for a text with giraffes and elephants over “Michael and the Crazy Circus”, and should come first in the search results. The method we used here only works if the search terms are fixed (controlled indexing). This could happen, for example, in specialized databases where the users are trained in how to use a search mask. In our example, a query modification would make sense: aside from “elephant”, a search for “pachyderms” as well as grammatical variants of these words would yield positive results.

There are a lot more search engines on the World Wide Web than just Google. For example, alternatives to Google often pay more attention to user privacy