CNAME Record

The Domain Name System (DNS) enables surfing on the World Wide Web as we know it: A user enters a domain name in the form of a URL in order to arrive at the desired website. The actual communication, however, occurs via an individual IP address. The DNS is based on zone file records. The actual name resolution uses the important types of A and AAAA records.

There many different types of records. In our comprehensive article on DNS records, we not only explain the records’ basic characteristics, we also provide a chart summarizing all the different types.

However, an IP address isn’t always linked with one domain name. Several names can also refer to the same IP address. To enable this, the DNS uses CNAME records.

What Are CNAME Records?

The DNS is based on a decentralized, organized server network. Name servers administer specific zones and have zone files at their disposal to this end. These are simple text files in which different DNS records are listed line by line. The records are composed of different types. To link the domain names with an IPv4 address, you need to choose type A record. With the CNAME type, a domain name is linked with an alias – i.e. another name under which the same offering can be reached.

The actual name is the one connected with the IP address in an A record. The advantage here is that should the IP address change, you only have to adjust the A record. Since all aliases in turn refer to this type A record (or type AAAA record), the CNAME records are immediately adjusted at the same time.

The CNAME designation is a portmanteau of “canonical name” – the name regarded as the standard. For this reason, the designation is also somewhat confusing, as the record doesn’t even establish the “actual” domain name, but rather its alias.

The CNAME Syntax

DNS records follow a standardized syntax with various fields:

- <name>: The domain’s alias appears in the first field.

- <ttl>: The “time to live” is the term for the time that a record may be held in the cache before the information has to be requested again.

- <class>: The class field is optional and specifies the type of network for which the record is valid.

- <type>: This field determines the record type – in this case, CNAME.

- <rdata>: The last field contains the information that the record actually refers to. Here, it is therefore the actual domain name.

The fields are simply separated by spaces and arranged within a line.

The time to live (TTL) specifies the duration of the information’s validity. The provider guarantees that the data is correct within this time period and for this reason may remain in the cache. If the time lapses, the information must again be recalled from the server. In practice, however, the field only appears rarely in the individual records. Instead, a TTL is globally determined for the entire zone. The individual records then take on this value.

Today, the optional field for class has only a historical value: While DNS was being developed, the networks Hesiod (HS) and Chaosnet (CH) – both no longer in existence – were originally both a possibility. Now only the internet remains. This is why one either finds in this place the abbreviation IN, or the field is completely omitted.

Names in the DNS records are always specified in the Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDNs) format. This means that the specification ends with a period. The reason for this is that FQDNs follow a domain’s complete path – and this begins (from the far right) with the root server. Because the corresponding field is empty, only the period separating the components from each other remains.

A CNAME record must always refer to another domain. It is not permissible to instead insert an IP address. What’s more, it is not permissible to use the defined alias in other record types. It is also recommended not to allow a CNAME record to refer to another CNAME record. Although that doesn’t lead to an error, it does make the zone file unnecessarily complex.

CNAME Example

In practice, a CNAME record looks like this:

In order for the reference to work through CNAME, an A and/or AAAA record must also be available in the zone file.

Both CNAME records refer to the A and/or AAAA record. The time to live is set globally for the entire zone (represented by the dollar sign) at 11,107 seconds, thereby totaling more than three hours.

CNAME Check: How You Can Find the CNAME Record

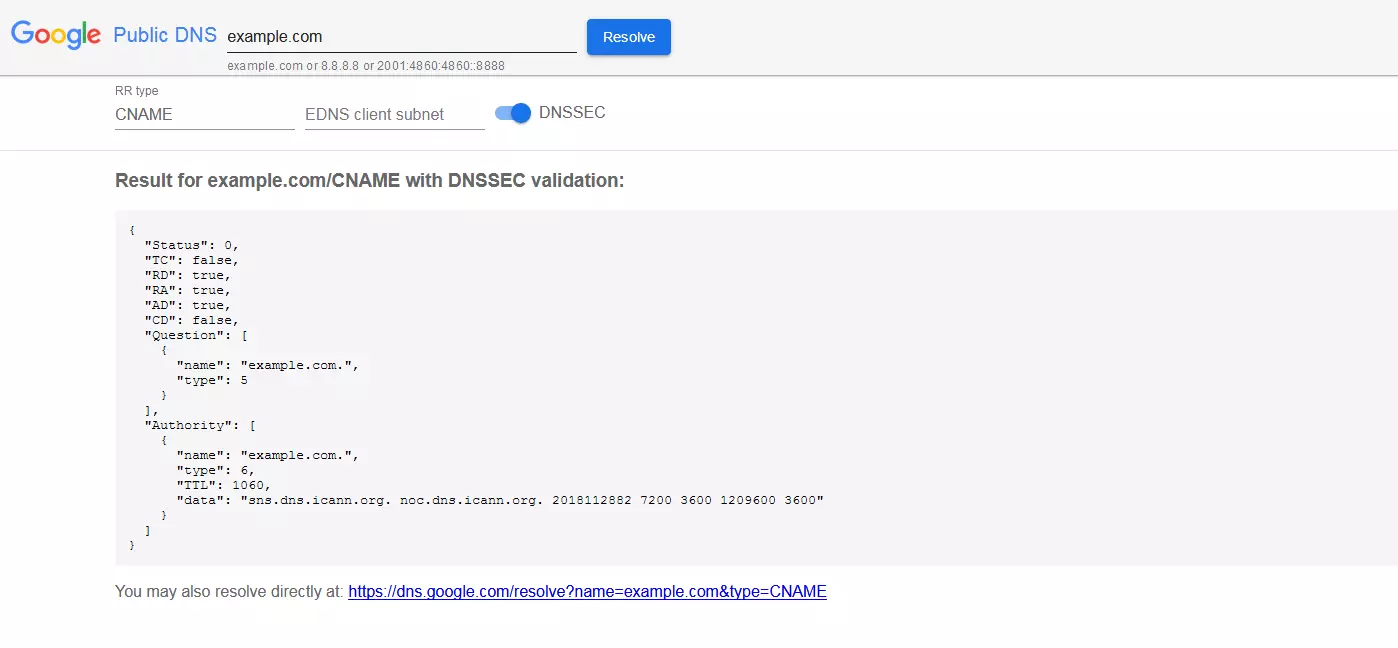

If you’d like to find out a website’s CNAME record, you can either turn to a special software program or simply use a web service for this purpose. With Public DNS, Google provides a separate DNS server that you can use to access the various website DNS records.

On the Public DNS website, you enter the desired domain whose CNAME you would like to check. On the following page, you should change the RR type (by default, this is set to A) to the CNAME record; then you have to click on the resolve button again to receive the result.

Both settings for the EDNS client subnet and DNSSEC can remain unchanged. The former is a mechanism that is supposed to capture the requestor’s location, and in this way deliver more efficient results – currently, however, it is only promoted by Google and OpenDNS. DNSSEC, on the other hand, guarantees the user that the information has not been manipulated by a third party who may have intercepted the communication unnoticed.